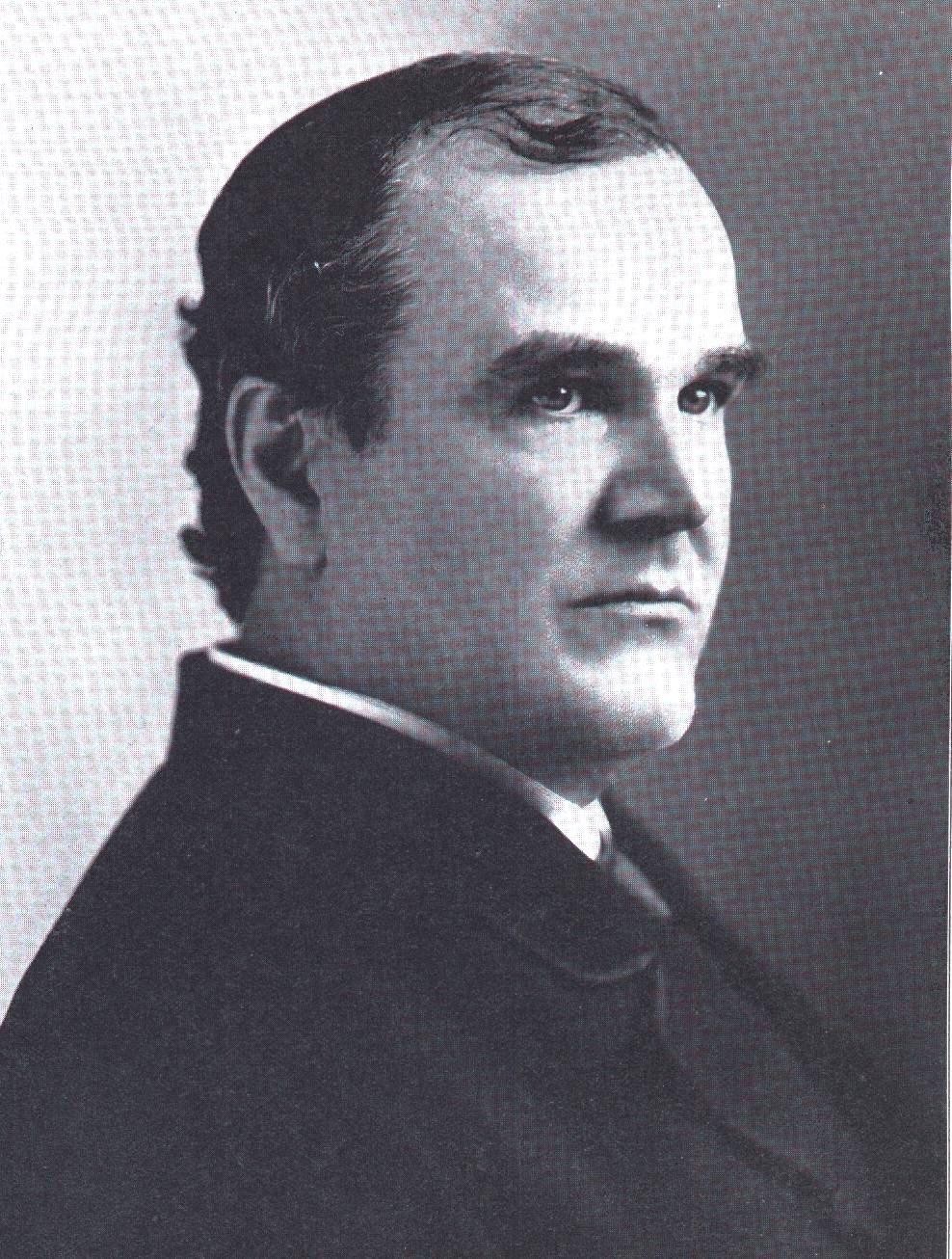

Reverend Doctor Edward McGlynn, 1837-1900.

By Mary McTamaney

This sentence was spoken by a Newburgh priest whose name and deeds have been largely forgotten by time.

Reverend Doctor Edward McGlynn served the Parish of Saint Mary, the Catholic Church on South Street, as its pastor in the 1890’s. His biography, Rebel Priest and Prophet written by Stephen Bell in 1937, has vanished from the shelves of most libraries, although I was able to borrow and read it a decade ago and a reprinted edition is available for sale.

Father McGlynn is a character whose voice comes echoing back along the streets of Newburgh for me every so often as I study our long three centuries. Newburgh has had several rebels, many priests and a few prophets. This one, who ministered from a working class parish in the center of the city came to us from the bigger metropolis of New York.

He was one of eleven children of an Irish immigrant family and was a brilliant student in his public elementary school. His teacher, his parents and his parish priest agreed he deserved a big break.

In 1850, they got him a scholarship to study in Rome, Italy on an academic path that would give him a high school and college education and ultimately ordain him as a Catholic priest. He did well and returned to lower Manhattan to serve in St. Stephen’s Church with a pastor who had been an ardent abolitionist in his youth. Together the young and old priest ministered to the many needs of their parish, both spiritual and temporal. St. Stephen’s is where Father McGlynn saw the constant parade of families asking for a chance at the American dream they or their ancestors had been pursuing for so long.

One night, Father McGlynn attended a lecture by the controversial social reformer, Henry George, who preached that land and tax reform could alleviate some of the inequities that kept a constant lower class in poverty. Reverend McGlynn, who had been advocating for his poor neighbors, embraced Henry George’s single tax concepts and joined the movement to advocate for legal reform. Father McGlynn was censured by his superiors at the New York Archdiocese and ordered to stay at St. Stephen’s, preach only the word of God to his own parishioners, and refrain from joining any social justice meetings.

He couldn’t bring himself to fall silent. He continued to write and speak about the imbalance in the economy and in opportunity. McGlynn was relieved of his duties and ultimately excommunicated from the Catholic Church. After many appeals and lobbying by his devoted followers, he was reinstated but banished from New York City.

The Catholic Church assigned Father McGlynn to what 19th century news reporters called a “sleepy little upstate town” where their hope was his activism would fade and he would serve quietly. Newburgh wasn’t all that quiet.

As always, it was a microcosm of American society where, especially in the 1890’s, the population was predominately industrial workers struggling for their daily bread. Rev. Dr. McGlynn was a magnet for other Newburghers of charitable minds and hearts. He became a leader in the ministerial association. He spoke eloquently for the rights of women to vote and change the direction of decision-making to support and strengthen families.

As a child of Saint Mary’s Parish (although long after the tenure of Father McGlynn), I listen for his voice this month reminding us of the value of all lives and the need to use heart and mind together to overcome oppression.

Edward McGlynn died in Newburgh on January 7, 1900 in the rectory still standing on South Street. His death was caused by a kidney infection that would be treatable today. His funeral mass at St. Mary’s was packed to overflowing that cold January and his colleagues in the Newburgh Ministerial Association held additional services for the next three days at packed churches all around Newburgh to allow his fellow citizens to pray for the rest of his kind soul.