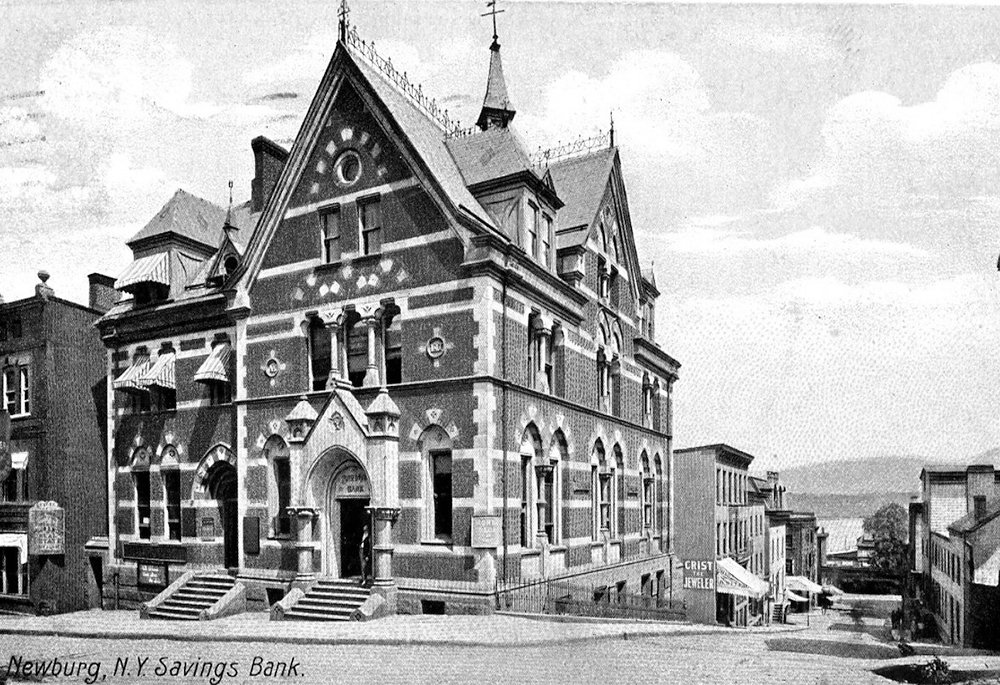

Newburgh Savings Bank – Corner of Smith & Second Street.

By Mary McTamaney

Bank failures were in the news this week as California’s Silicon Valley Bank and then New York’s Signature Bank were in danger of having insufficient funds to cover their depositors’ accounts.

First Republic Bank is also reported to be in jeopardy. Account holders in these banks will be protected from losing their funds by state and federal safety protocols instituted after past bank panics.

Once upon a time, “the full faith and credit” of a bank rested not in government agencies like the FDIC, but in the honesty and skill of the local men who owned and operated the banks. That is what depositors understood when they entered the doors of Newburgh banks for this community’s first 125 years.

After a post-Revolution period when borrowing in Newburgh was done privately between neighbors or as a business transaction among associates, Newburgh’s first incorporated bank opened its doors in 1811. It was the Bank of Newburgh, modeled on a small scale to Alexander Hamilton’s 1784 Bank of New York. The Village of Newburgh had been incorporated in 1800 and grew quickly as a commercial center on the main trading route – the Hudson River. Soon, investors began road building projects to move trade goods in and out of their bustling port. So successful were the trade opportunities afforded by having a commercial bank that the Bank of Newburgh opened a branch in Ithaca, New York, a terminus of one enterprising early roadway that had been financed largely by Newburgh businessmen. In 1820, one could step off a wagon or stagecoach on the main street of Ithaca at the foot of Cayuga Lake and see a Bank of Newburgh proclaiming this village’s importance.

The Bank of Newburgh was followed in the early 19th century by The Highland Bank, The Powell Bank, The Quassaick Bank and the Newburgh Savings Bank, all operating in the decades before the Civil War. Each had deposited assets of well over $150,000. More importantly, each had officers and trustees who were Newburgh residents with business interests in their hometown.

The Powell Bank invested enough to help save Newburgh from economic collapse in 1825 when the Erie Canal opened and created a sudden shift in commerce from roads to water. All the goods including farm produce and construction materials that had rolled into this village on turnpikes was suddenly seen floating past our docks on barges that had come down the Erie Canal and were destined for Manhattan. Officers of the Powell Bank helped to finance alternative enterprises that kept Newburghers employed. Still, the Powell Bank did have to close in The Panic of 1857 when its trustees voted to pay off depositors and then divest the balance of capital to rescue projects around Newburgh. By then, Newburgh had four other banks including the largest, The Newburgh Savings Bank, built in 1852. Its charter, as its title suggests, was to encourage a culture of savings for the future. It succeeded and its deposits soon outpaced all other local banks. The grandeur of its headquarters on Smith Street at the corner of Second Street proclaimed its status. So lovely was its 1852 bank headquarters, designed and supervised by Newburgh architect Calvert Vaux, that the village’s common council took a long-term lease for a new council chambers outfitted in the upper floor. Village, and soon city, aldermen and committee members met inside the tall windows looking out with pride on the growing traffic along downtown streets, rails and river piers. Descriptions of Newburgh banks written over a century ago always describe their elegant and secure “counting rooms.” Inside those paneled walls, clerks were overseen by bank treasurers each and every day making sure the tallies of every transaction were correct before they locked up for the evening.

It is hard to imagine the officers of the locally owned and staffed banks of 19th century Newburgh ever shifting their depositors’ (their neighbors’) assets to shaky investments like cryptocurrency.