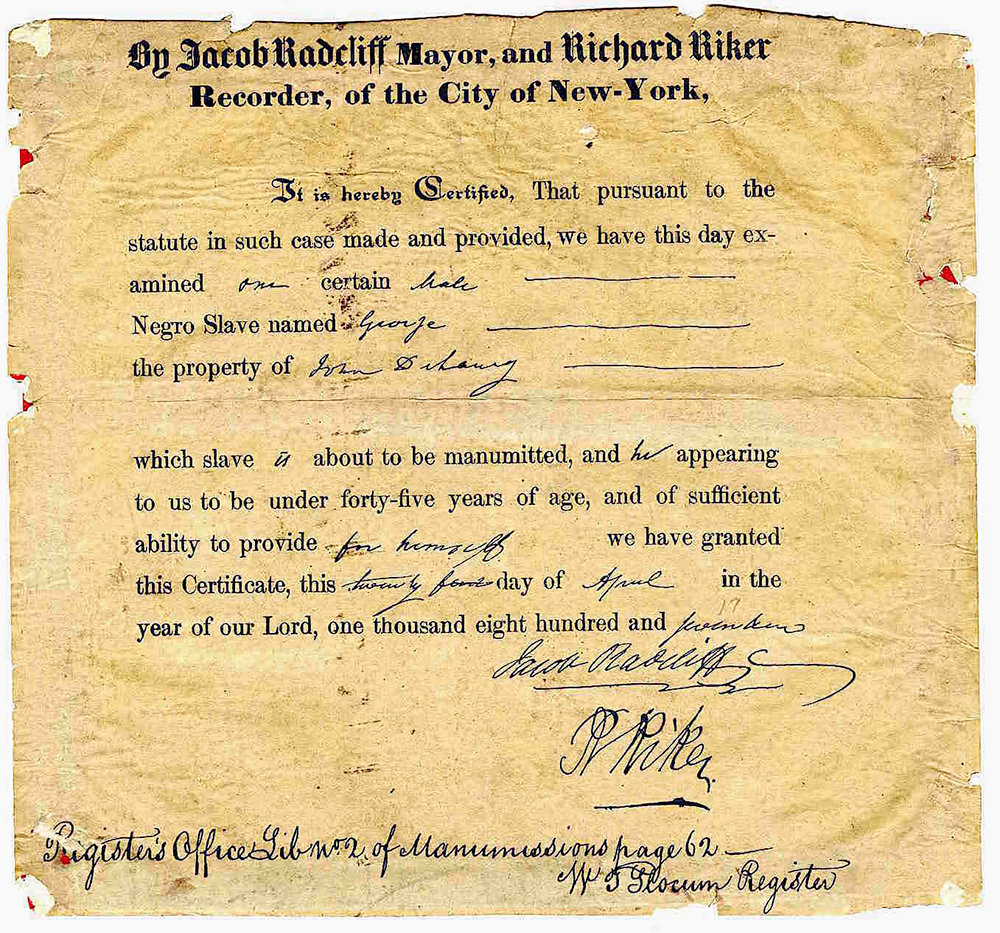

One precious “freedom paper” - the 1817 manumission document proving to all that a man named George was an independent citizen of New York (from the Columbia University archives).

By Mary McTamaney

Since 1976, February has been designated on the national calendar as Black History Month.

The commemoration began fifty years earlier with a national establishment of Negro History Week to honor the February birthdays of both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Not only had Lincoln and Douglass been born at this time, but February includes these milestones as well: February 1st is the date in 1960 when Greensboro, N.C. college students began their sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter; the 15th Amendment granting blacks the right to vote passed on Feb. 3, 1870; the NAACP was founded in 1909 on Feb. 12; Malcolm X was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965; W.E.B. Dubois’ 1868 birthday falls on Feb. 23 and on February 25, 1870, America’s first black senator, Hiram Revels, took his seat with his peers.

Yet, beyond the national stories that we have come to know, there is a lot to be proud of in the African-American history of our own city through the years. Yes, in parish and village days, Newburgh had residents without citizenship held as slaves.

Eighteenth century farmers in the town of Newburgh bought slaves to labor in their enterprises. Down in the commercial center of the village along the Hudson River, the picture of slaves loading wagons and driving horse teams here at our docks was a common sight into the turn of the 19th century. New York State was slow to free its slaves and did so in a gradual process between 1799 and 1827.

What our community can be proud of this month is the story of free people who chose Newburgh as the place to build their independent lives. After manumission (NY State’s legal end to slavery), many freemen came here with good skills learned on estate farms throughout the Hudson Valley and found paid work. Several even went into business for themselves. Seamstresses, blacksmiths, horsemen, carpenters, chauffeurs and cooks joined other workers in our village in the three decades before the Civil War.

Washington Street was the primary neighborhood where Newburgh’s African-American community began to buy land and build modest houses. In the 1850’s, three teachers, all people of color, are listed in our census: Stephen Ajou, Jerhamiah Decker and Elizabeth Waters. John Hornbeck was a steamboat cook; Ann Wynkoop was an ice-cream maker and vendor; Alberto Ovedo, born in Cuba, was an apprentice silversmith; John Schoonmaker was a blacksmith; Dinah Kendall owned a pickle-making business and her son Adam Kendall was an apprentice wagon maker; Peter Adams and Henry Walsh were both shoemakers; William Lloyd was a painter; Diana Paine, Peter Richardson and Sarah and Mabel Simonds all ran saloons; Charles Brin was a barber and so was William Jackson and father and son Stephen and Sylvester Wood; Joseph Bruyn was a farmer with land worth $3,000 – a significant holding in 1850; Titus Johnston and George Simon were mariners, some of many men who shipped in and out from the Port of Newburgh on our merchant sloops. George Seaman, a coachman for noted homeopath, Newburgh’s Dr. William Culbert, went on to be become America’s Minister to Haiti.

Of special interest in Newburgh’s African-American story is a man named Elisha Hawkins, born in Virginia as a slave but allowed to study not only reading and writing there but to informally study the arts of medicine and dentistry. One of his masters brought him north on occasion and he attended missionary conventions while in Massachusetts.

While still a slave, Hawkins received his license to preach and in 1849, after buying the freedom of his wife and daughter in Virginia for $300 (his southern master had freed Hawkins himself in 1848) he took the job as pastor at Newburgh’s Shiloh Baptist Church. His pastorate was to a Negro congregation but he continued to practice medicine intermittently for Newburghers of all races.

State and federal census data is the best source of accurate information on who lived in our community through the decades. One encouraging fact found in reading Newburgh’s census and other records of the 1850’s is that many children of color were listed as students. Not enough in those days of child labor, but significant numbers to have given birth to a core population to honor during Black History Month.