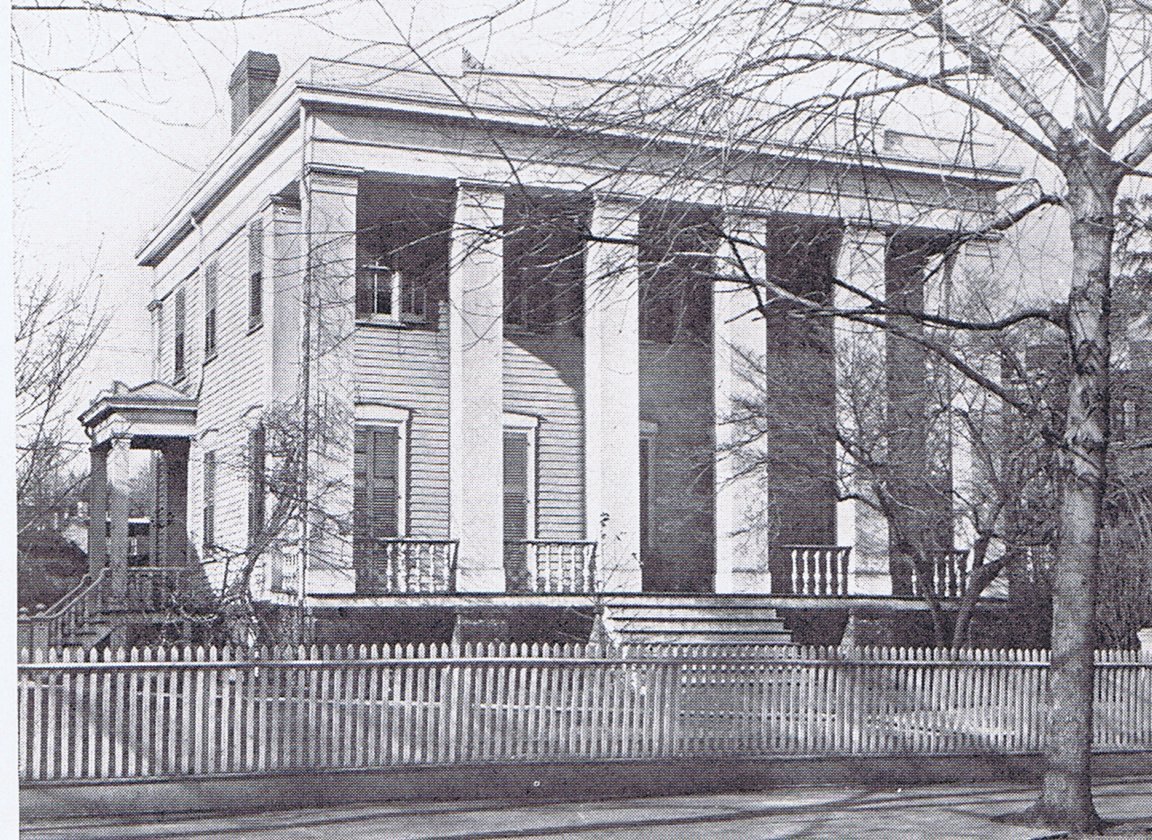

Mayor Clark’s house on Liberty Street, now the site of the Post Office

By Mary McTamaney

Watching interviews on television this past season has revealed many of the reading interests of journalists, public figures and a random sampling of Americans who are expert in various fields. When the interview gets a bit redundant or boring, I have done what many viewers have admitted doing – I tilt my gaze and look for the titles of books in home libraries.

One that shines out, partly because of its unusual thickness, is the recent biography of Ulysses Grant. It was written by historian Ron Chernow who wrote about Alexander Hamilton in 2004. We know that splendid research led to the hit musical Hamilton! Perhaps there is an aspiring Newburgh poet and composer who will tackle Grant as a subject for the Broadway stage. His was also an improbable and heroic life. The President and former Union Civil War General had a Newburgh connection so it would be a fitting choice.

Ulysses S Grant was an Ohio boy educated at West Point (1839-1843) where a clerical error on his nomination form to the military academy put the floating letter S between his first and last names. Ulysses was actually his middle name having been registered by his father at birth in 1822 as Hiram Ulysses Grant, then never using that first name.

He may have visited Newburgh during his years as a cadet but he became the focus of local news a quarter century later when he came for a visit with our first mayor, George Clark. Mayor Clark had been lobbying General Grant right after his election to the presidency to invest federal dollars in building a road from West Point north along the Hudson River shore. Grant had been visiting his alma mater and Clark went down to West Point, then a river boat trip, with city leader and attorney Joel Headley to meet with the new President.

Grant promised to visit Newburgh which he did a year later on August 7, 1869. Grant arrived that morning (after spending the preceding night at West Point) on the small steamboat, the M. Martin which had been his dispatch boat when he commanded the Union Army (a detail that Newburgh leaders thought would please him). He was the guest of Mayor Clark and, after touring the city and making a pilgrimage to Washington’s Headquarters, he went to the mayor’s gracious home on Liberty Street at the head of Second Street. A banquet table had been set up through the length of the mayor’s house so that many civic leaders could dine with the President and have their chances to convince him of the region’s importance.

The shoreline road from West Point north eventually proved too large an engineering job for any of the interested parties to tackle, but Newburgh made a good impression. It was quickly growing into a Hudson Valley industrial hub after the war and President Grant saw progress all around him.

Progress was a campaign promise of the former general. As a military leader, he had followed President Lincoln and his mission to unite America as one fully free nation. With Lincoln’s assassination, the racist Andrew Johnson entered the presidency and so Grant had much damage to repair. He set to work restoring goals of Reconstruction and ushered a Civil Rights Act through Congress that included voting rights. He established the Department of Justice in the face of a violent and rising Ku Klux Klan. He appointed the first Indian commissioner to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a New York Seneca. Grant was a tactician and Newburgh was wise to lure him north for a visit early in his presidency.

Like today, political parties were in a state of confusion. Republicans had become the progressive party that elected Abraham Lincoln and many post-war Democrats were pushing for a restoration of the Confederacy. Here in the north, a second wing of that party, the “War Democrats” as they had been dubbed were seeking the goals of Reconstruction. Grant’s first term may have been guided by many voices like those of the men he met in Newburgh.

Ulysses Grant died at age 63 here in New York State. After two terms as President, he had lost his savings in a Ponzi scheme at the time he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He desperately wanted to provide for his wife and children so he began writing his memoirs, hoping they would appeal to Americans and bring income to his widow. To do that writing he rented a quiet cabin in Moreau, NY, up in the lower Adirondacks at the encouragement of his friend, Mark Twain. He hoped the fresh mountain air would prolong his life enough to finish his book. He succeeded, although debilitated by terrible pain and his book sold over 300,000 copies, sustaining his family into the future.

President Grant had a final connection to Newburgh. His body was buried, according to his wife’s wishes, in Riverside Park in New York City. On the 75th anniversary of his birth, the beautiful (and now famous) Grant’s Tomb was opened there to be his final resting place. Its architect was John H. Duncan, the designer of Newburgh’s Tower of Victory on the lawn of Washington’s Headquarters. Both buildings have been restored to their original grandeur to allow Americans to spend reflective moments remembering leaders who carried us forward in times of trouble.

To see the outpouring of respect America had for Ulysses Grant, watch the short video posted on YouTube by Albert Garzon. “General Grant’s Funeral March.” Mr. Garzon resurrected the old sheet music and played it on his piano for us. Beautiful presentation.